Hotels and movies go together like thrillers and popcorn, writes Kristofer Thomas, as Sleeper takes a look at the way hospitality projects are portrayed on the big screen.

There is a two-way relationship between hotels and films: a starring role in an acclaimed release can see a hotel become an icon, but the reverse is also true. In the right hands a carefully considered hotel setting can elevate a narrative beyond any performance delivered within its walls, and in some cases acts as an integral tool in the delivery of theme and subtext. Buildings full of strangers in strange lands are rich veins of drama, conflict, and connection all at once, and across eras, movements and national borders, directors have returned to hotels – real or otherwise – as tried and tested stages.

An example: The Bellagio, formerly The Dunes, has appeared as a symbol of both of Las Vegas glamour, as in Ocean’s Eleven (2001), and so too the city’s paranoid underbelly, when it hosted Hunter S. Thompson and a room full of police officers for the District Attorney’s Convention in Fear and Loathing (1998). in this sense, a hotel’s contribution can range from signalling a character’s class, desires and taste to providing a guiding purpose and ideal. And, thanks to the efforts of the hotel design community, these environments often come readymade with elements of symmetry, scale and lighting conductive to stylish direction.

If you, the reader of this hotel design website, find yourself working from home at the moment – as much of the Sleeper staff do – and need a film or three to take your mind off these trying times (but still have it sort of count as work) then here’s a list of the best.

The Shining (1980)

It appears on every list to cover this subject for good reason: Stanley Kubrick wove the presence of The Overlook Hotel so tightly into The Shining that it became the antagonist. A juxtaposition between the Torrance family’s complete isolation and our familiarity with hotels as bustling centres of activity sets the ominous tone, before the real horror unfolds as a slow burn tour through the hotel’s decaying past and present. Throughout the first half, Kubrick sets out the various floorplans of Colorado’s Stanley Hotel by having the camera wander slowly through its halls to establish its form, only to break these paths and reconnect them elsewhere later on, creating a sense of spatial disorientation that works silently to underscore the more obvious horror elements in Kubrick’s masterpiece. Vector-patterned carpets are yet to recover.

The Lobster (2015)

Yorgos Lanthimos’ black comedy The Lobster recast Ireland’s Parknasilla Resort & Spa as a dystopian processing centre for single people in a world of relationships. You never know who might be staying a few doors down the hall, but in this stately riverside retreat guests range from the love of Colin Farrell’s life to a maid with ideas to turn him into an animal. It follows a line of films that treat the concept of hotels – buildings designed to host chance encounters between strangers passing through – as inherently weird and surreal, which started with the ambiguous identity games of Last Year at Marienbad (1968) and runs up to the stop-motion-business-trip oddity of Anomalisa (2015).

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Like all good hotel designers, Wes Anderson knows the importance of hotels having character. And like the best he realised that, beyond aesthetics, service and comfort, a property needs a soul – an identity to which guests are drawn on a personal level. Any other title for his ninth film would have dismissed its hero, The Grand Budapest herself, a brutalist structure atop a mountain that owner Zero Moustafa reveres as living, breathing legend. Despite the bulk of the film being shot in a Görlitz department store, the set created within draws from authentic interiors Anderson encountered on a tour of Eastern European grand hotels, which, when combined with the director’s signature maximalism, makes for a compelling stay. “Why do you want to be a lobby boy?” Moustafa asks his new hire. “Who wouldn’t, at the Grand Budapest sir?”

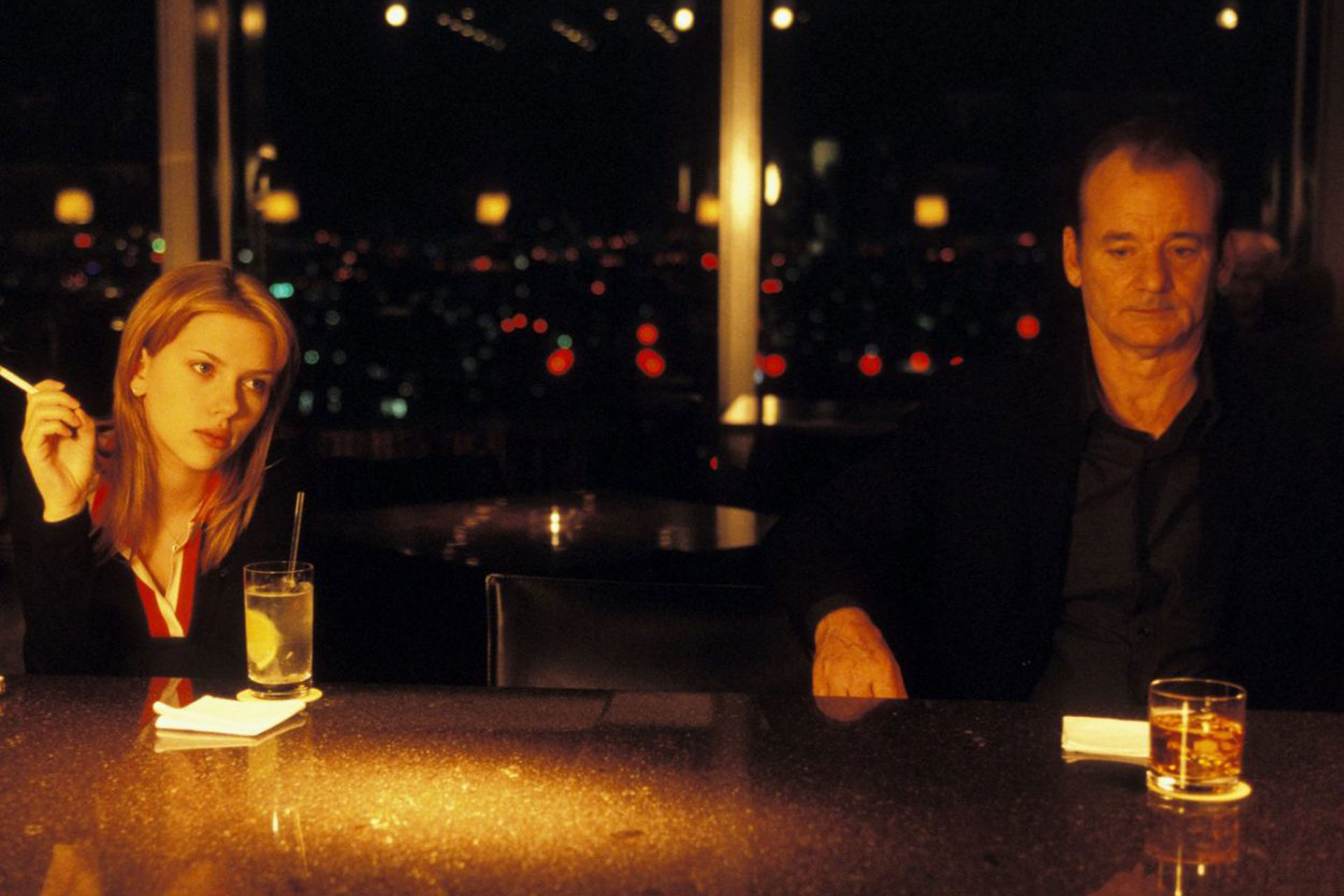

Lost in Translation (2003)

A melancholy Park Hyatt Tokyo speaks louder of an overarching 21st century isolation philosophy than either character in Lost in Translation’s minimal script. Designed by Pritzker Prize winning architect Dr. Kenzo Tange with interiors by John Morford, the property struck gold when it was selected by Sophia Coppola as the setting for her breakout crystalline drama; its sleek, modernist interiors gifted two-hours free screentime in a film that would go to be something of a document for mid-2000s malaise. Coppola would revisit the motif seven years later, dropping an actor in the midst of an existential crisis and his estranged daughter into the pool of Chateau Marmont for the underloved Somewhere (2010).

Barton Fink (1991)

Hotel Earle is hell. Wallpaper peels from the walls; the guests next door are loud beyond reason; the place is fully booked, yet we only ever see the ghostly row of shoes left outside each room; and the hallways spontaneously burst into flame. In the Coen Brother’s writer’s block fever dream the hotel is temporary home to the eponymous Barton Fink, a man riddled with anxiety and insecurities that manifest as the guest experience of nightmares. Whether he gets to leave or not depends on your reading of the final image, and how you feel about hotel art from a time long before curation services were the norm.

James Bond (1962-)

Fontainebleau in Goldfinger; Taj Lake Palace in Octopussy; The Langham in Goldeneye – 007 has refined taste and zero loyalty points. With Bond’s list of stays reading like the contents page of Sleeper before Sleeper was a thing, he’s something of a pioneer in the hotel design journalism community, having immortalised the Hotel Danieli bar (Moonraker, 1979), The Peninsula Hong Kong’s pick up service (The Man With the Golden Gun, 1974) and the British Colonial Hilton Nassau’s pier along the way. The last is a JB favourite – he stayed in Thunderball (1965) and Never Say Never Again (1983), meaning he’s now only 4800 points away from a free night.

Ex Machina (2014)

Providing a suitably modernist setting for Alex Garland’s artificial intelligence drama, the Juvet Landscape Hotel on the northern coast of Norway reflects the film’s flirting with futurism by way of a progressively designed project by Jensen & Skodvin Architects. Full of straight lines, sharp edges, timber and concrete, the 9-key hotel contains the entire plot; its minimalist interiors a deceptively serene backdrop for the increasingly cryptic plot. Views over the surrounding Norwegian forest, meanwhile, visually anchor the film’s preoccupying theme of man vs natural order.

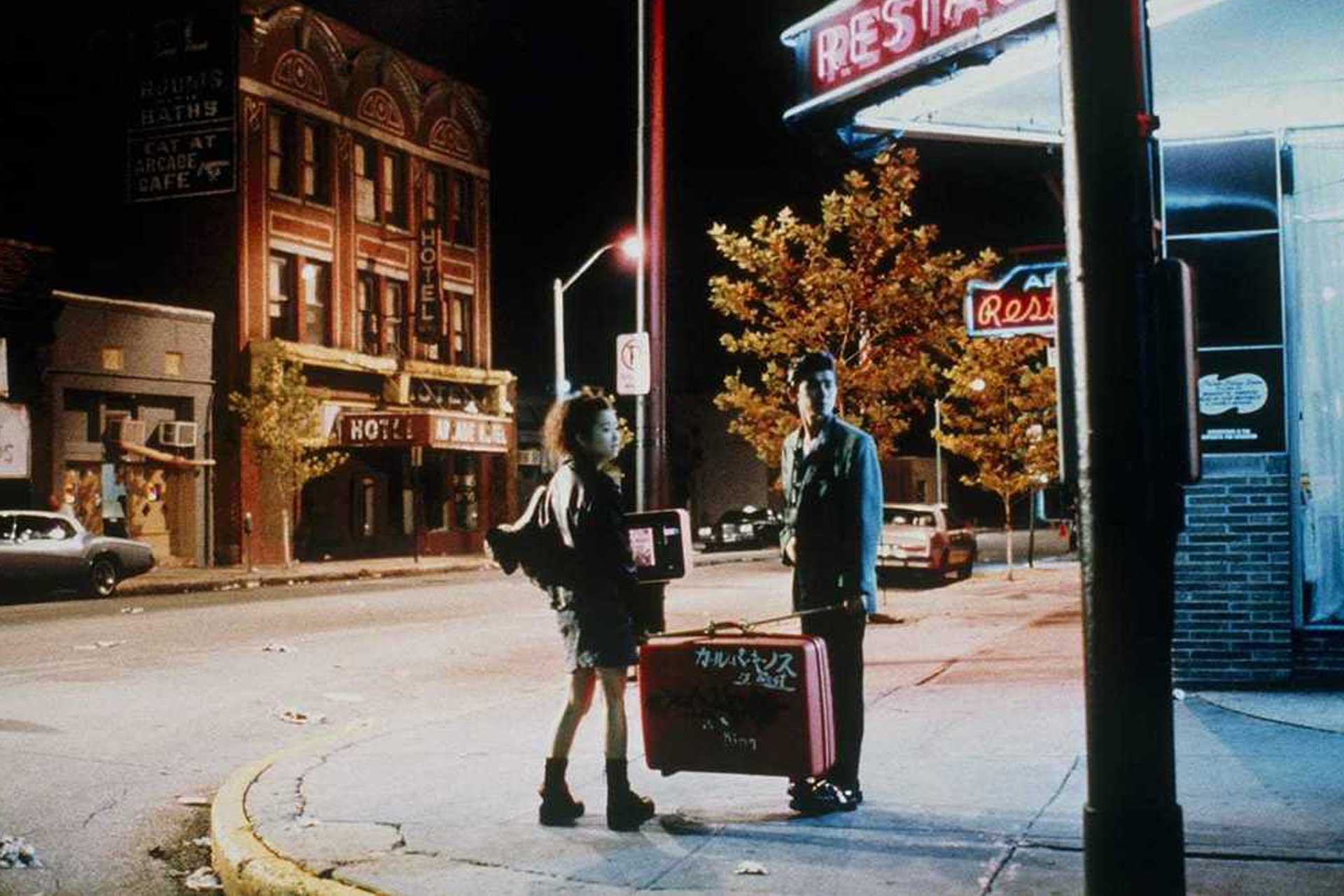

Roadside Motels

From Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960) to No Country for Old Men (Coens, 2008) via Lolita (Kubrick, 1962), Paris Texas (Wenders, 1984) and Wild at Heart (Lynch, 1990), the American roadside motel has become a kind of cinematic shorthand for intrigue. Liminal spaces between starting point and destination where anything can happen, many a cinematic journey has found itself drawn to the nondescript roadside accommodation for some R&R, only to stumble across something unexpected – be that a killer down the hall or a moment of self-reflection. All three stories in Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train (1989) orbit the dilapidated Arcade Hotel in Memphis, where there’s no TVs but plenty of Elvis portraits, and each strange tale functions to highlight the sense of purgatory and just-passing-through secrecy of motel life.

The Plaza New York

There are a handful of hotels that, having starred in so many films, might soon demand outstanding contribution awards of their own. LA’s Millennium Biltmore is a Hollywood favourite with over 100 credits to its name – not least Chinatown (1974), Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Ghostbusters (1984) – whilst Beverly Wilshere to the east has played alongside the casts of Pretty Woman (1990), To Live and Die in LA (1985), and Frost/Nixon (2008). Few contemporaries, however, boast the range of The Plaza New York. Roles in North by Northwest (1959), The Great Gatsby (2013), Crocodile Dundee (1986) and a cameo alongside a future president in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992) have seen the Henry Janeway Hardenbergh-designed hotel become something of a veteran of American cinema.

Honourable Mentions

Southern California’s Hotel del Coronado welcomed Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon for Some Like it Hot (1959); having opened as the largest resort in the world in 1888 it today forms part of Hilton’s Curio Collection. Hotel Mumbai (2019) tells the story of the property’s head chef Hemant Oberoi as he responded to the Mumbai terrorist attacks in 2008; find an interview with Oberoi about this night in the latest issue of Supper. The exterior of The Great Northern Hotel where Agent Cooper stays in throughout Twin Peaks (1990) was filmed at the Snoqualmie Falls Lodge in Snoqualmie, Washington; remodelled in 1988 as the Salish Lodge & Spa, today it serves a Dale Cooper cocktail along with “damn fine coffee and pie” inspired spa treatments. Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo began their brief life on the lam together at Les Rives de Notre Dame in Paris in Jean-Luc Godard’s A Bout de Souffle (1960), and Venice’s palatial Hotel Gabrielli doubled as the Europa Hotel in which Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie took their last holiday for Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973). Last but not least, the maroon flight tubes at JFK that Leonardo Dicaprio passes through during Catch Me if you Can (2002) were restored over the last decade as part of New York’s TWA Hotel, a 512-key conversion of Eero Saarinen’s iconic terminal building.

Did we miss any? Let us know @Sleepermagazine

Related Posts

17 March 2020

Sleeper presents – top hotel openings of 2020

18 March 2019

FEATURE: AHEAD Global names world’s best hotels

15 December 2017