Meeting… Ole Scheeren

The founder of Buro Ole Scheeren reveals designs for his first fully integrated hospitality project and discusses the importance of bringing nature back to the built environment.

While most of the world has grappled with remote working and communicating through a screen over the past 18 months, some forward-thinking types have revelled in the fact that it’s business as usual, already accustomed to this so-called new way of life by the nature of their set-up. For Ole Scheeren, the pandemic hasn’t had much of an impact on the running of his eponymous studio. Of course there’s less travel, but in terms of day-to-day operations, there’s little change. “I’ve been working virtually for the past 20 years, so our office was entirely used to the system that the whole world had to adopt,” he explains, speaking to Sleeper via Zoom from his office in Berlin. “I was travelling so much that I could not be with my offices all the time; we already had a daily routine of working virtually with each other in addition to the physical encounter, so it was a very simple transition.”

With offices in Hong Kong, Beijing, Bangkok, New York, London and Berlin, and projects in all corners of the globe, Scheeren admits that his pre-pandemic schedule was a little extreme: “I was on an aeroplane three times a week, visiting three continents every month,” he notes, adding that the enforced stay-home has been an interesting life lesson. Though he’s more stationary for the time being, Scheeren doesn’t seem the type to sit still for long. The German architect has travelled extensively through his life, with every experience – from backpacking through rural China at the age of 21 to studying at the prestigious AA School of Architecture in London – coming together to shape the way he approaches design. “Over the course of my life, I’ve had the opportunity to visit over 100 different countries and simply observe,” he explains. “I grew up with architecture so from very early on I had an understanding of what space does for people. I’ve always been fascinated by the psychology of spaces and how people use the buildings we create; I believe it’s very important to incorporate that context into our designs.”

Scheeren’s early exposure to the world of architecture stems from his father, also an architect, and by the age of 14 he was in the studio getting a head start on his future career. An innate curiosity about the world and the belief that architecture could better contribute to its surroundings led to stints working and studying in New York, London and Lausanne, but it was landing a job with Rem Koolhaas at OMA that really set him on the road to success. “It was a fairly important period in my early career,” Scheeren explains. “Altogether I worked with Rem for almost 15 years and in that time I took on a variety of different projects. I was in charge of the Prada flagship stores in New York and Beverly Hills, which played on the experiential idea of architecture, and later on I built the entire Asia business for the company and led the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing. My projects spanned from small scale to one of the largest buildings ever constructed, so that gave me the experience to do what I’m doing today.”

In 2010, Scheeren went solo and founded his own studio, making the bold decision to remain in Asia to differentiate from the Western firms who were exporting their designs to the East. “I wanted to find a much more direct engagement with Asia and so headquartered the company out of Hong Kong,” he notes, going on to point out the irony that he’s now found himself with a rapidly growing portfolio of projects in Europe and North America. This method of working paved the way for broad scope of projects, both territorially and in terms of typologies: for example, there’s the archipelago cinema – a screen and floating auditorium in Thailand’s Nai Pi Lae Lagoon; Fifteen Fifteen, a high-rise residential development in Vancouver; and Shenzhen Wave, a new headquarters and innovation centre for a leading technology company. “It’s very exciting to move between scales, to move between different architectural typologies and to move between different cultures of the world,” Scheeren continues. “We have a great team of 100 architects who collaborate globally across continents and help inform one project through the diverse experiences of another; it’s become a very interesting dialogue that we’ve established.”

This idea of dialogue is one that touches every aspect of Scheeren’s work, not only through communication with his team but between the buildings he designs, their surrounding environment and the people who use them. “Architecture is a highly specific discipline; it doesn’t look the same everywhere and shouldn’t serve the same purpose,” he explains. “Each project is a very specific investigation of a place, of a culture, of a client, of a vision of what it can contribute. This diversity and multiplicity really drives our interest.”

While there’s diversity in the scope of projects, they share a common goal in aiming to shape the way people interact with spaces. “Architecture should be an active part of the city and of the urban environment, it should enable and empower its users in many different ways and I believe that we have a responsibility to make a lasting contribution to the public domain,” Scheeren adds. “With every project, we have to investigate how we can contribute to the way people interact with architecture and space, and how it can add to their lives; I believe architecture is an important component in the creation of experiences and memories.”

The creation of memories is regularly the talk of hospitality design, and Scheeren has had a hand in a number of projects over the years, including the Guardian Art Centre in Beijing, a gallery and exhibition venue that also houses The PuXuan Hotel; Duo, a mixed-use tower complex in Singapore with an Andaz on the upper floors; and MahaNakhon, another mixed-use skyscraper, this time in Bangkok and slated to include a hotel. With so many of the studio’s projects incorporating a variety of uses, how important is a hotel in this context? “What’s interesting about a hotel is that it always creates an anchor for a mixed-use development; it provides a social melting point where people come and go and can be an important part of a larger urban ecosystem,” he enthuses. “Hotels play a key role in activating and animating parts of urbanity.”

And what of mixed-use development in general, is there increased demand from clients to integrate more and more elements? “Our lives are an increasingly interconnected world where things no longer exist in the classical separations of this is where you work, this is where you sleep, this is where you eat; activities are coming to integrate and overlap in a very explicit way,” Scheeren explains, adding that the pandemic has undoubtedly accelerated a shift that was already in play. “This is where the role of architecture comes in, in bringing all those different aspects of life together. If you look at a lot of my work, it is an investigation of how we bring things closer together – not only work and life – but how we can bring the experience of nature to the built environment; Abaca is a very explicit exploration of that.”

“I grew up with architecture so from very early on I had an understanding of what space does for people. I’ve always been fascinated by the psychology of spaces and how people use the buildings we create.”

Abaca Resort is the newly-announced project that will bring Scheeren’s ideas on architectural discovery to life. Located in Cebu in the Philippines, the 125-key hotel builds on an existing property on the island of Mactan, and is inspired by the region’s traditional vernacular and tropical landscape. “This project tells a story of discovery and surprise, a story of wonder and curiosity, a story of the language of architecture and the power of tropical nature,” he confirms. “It is a journey through the rainforest and the exploration of habitable structures with places of rest and repose.”

Having been approached by Abaca Group and Cebu Landmasters to collaborate, Scheeren spent time at the existing nine-bedroom hotel, an experience that came to shape his eventual design. “During my stay, there was a feeling of intimacy that allowed me to have this very personal feeling of being in a particular place,” he explains. “That was the inspiration; how can we reinvent this spirit on a different scale, in a different way for the new hotel?”

The answer, according to Scheeren, lies in creating spaces that unfold and reveal themselves over time. “The way I have imagined the experience is as a succession of discoveries, like a journey through the jungle where you suddenly find a path through the greenery and it happens to lead to the lobby,” he reveals, “or you descend into a grotto that opens out to waterfalls, pools and gardens; it takes you on a whole journey of individual moments through the project.”

It may sound like the stuff of fantasy, but the blueprints show just what Scheeren describes, with lush landscaping, cascading waterfalls and tranquil clearings in the rainforest sheltered by tree canopies. Punctuated by pockets of greenery, the newbuild tower element is a vertical lattice of arches that stack, recess and protrude to form shaded balconies and floating pools in the sky. At ground level, the building is defined by arched colonnades that recall ancient archaeological structures rooted in the jungle, with multi-level terraces and water basins offering intimate areas for gathering.

“What’s interesting about a hotel is that it always creates an anchor for a mixed-use development; it provides a social melting point where people come and go and can be an important part of a larger urban ecosystem.”

Despite a ten-fold increase in keys, Scheeren is confident he can retain the intimacy and sense of place he experienced on his first visit. The layered topography with a series of semi-private spaces at each level was a conscious decision, as was the way in which the guestrooms are designed as if individual villas carved into the rock. The curves of the façade extend inside to the doorways and selection of FF&E, and each room offers sweeping views of the ocean, perfectly framed by the arched windows and hanging gardens.

Cebu’s rich history of craftsmanship will also play an important role in the project, with local artisans, materials and construction practices all taken into consideration. “We want to work with local stone and locally-available materials,” confirms Scheeren. “This has ecological benefits but it also makes for a more interesting story if a place is rooted in local culture. There are other elements such as the furniture and fabrics; Cebu has a strong tradition in weaving, so this will become part of the story too.”

While the studio has a vast portfolio of projects spanning the globe, Abaca Resort marks the first time it has designed a hotel in this way, taking on architecture, interiors and landscaping for a fully integrated experience. This approach is one that Scheeren believes is becoming increasingly important. “When there’s one team hired to design the shell and another to do the interiors, there’s a lack of integrated vision,” he believes. “We have quite a few projects at the moment where we are providing a holistic service, creating not only the architecture but the interiors and landscape. Abaca Resort is a great example of what we can do and by approaching projects as a fully integrated plan, it results in a better experience for guests.”

As talk turns to the future, Scheeren reveals that he’s working on a number of hotels, some standalone, some forming part of mixed-use developments. There’s an urban resort with Hyatt, and a soon-to-be-announced project with IHG. And while the all-important guest experience is at the heart of the studio’s concepts, Scheeren is mindful of the role of the operator. “I think it’s important to have the operator – the people who will be running the hotel day-in day-out, long after construction has finished – on board from the very beginning,” he notes. “Of course that’s not always possible, but I believe that the more you can plan a project as a fully integrated vision, the stronger it will be, the better it will work operationally, and the more exciting the experience will be.”

“I believe that the more you can plan a project as a fully integrated vision, the stronger it will be, the better it will work operationally, and the more exciting the experience will be.”

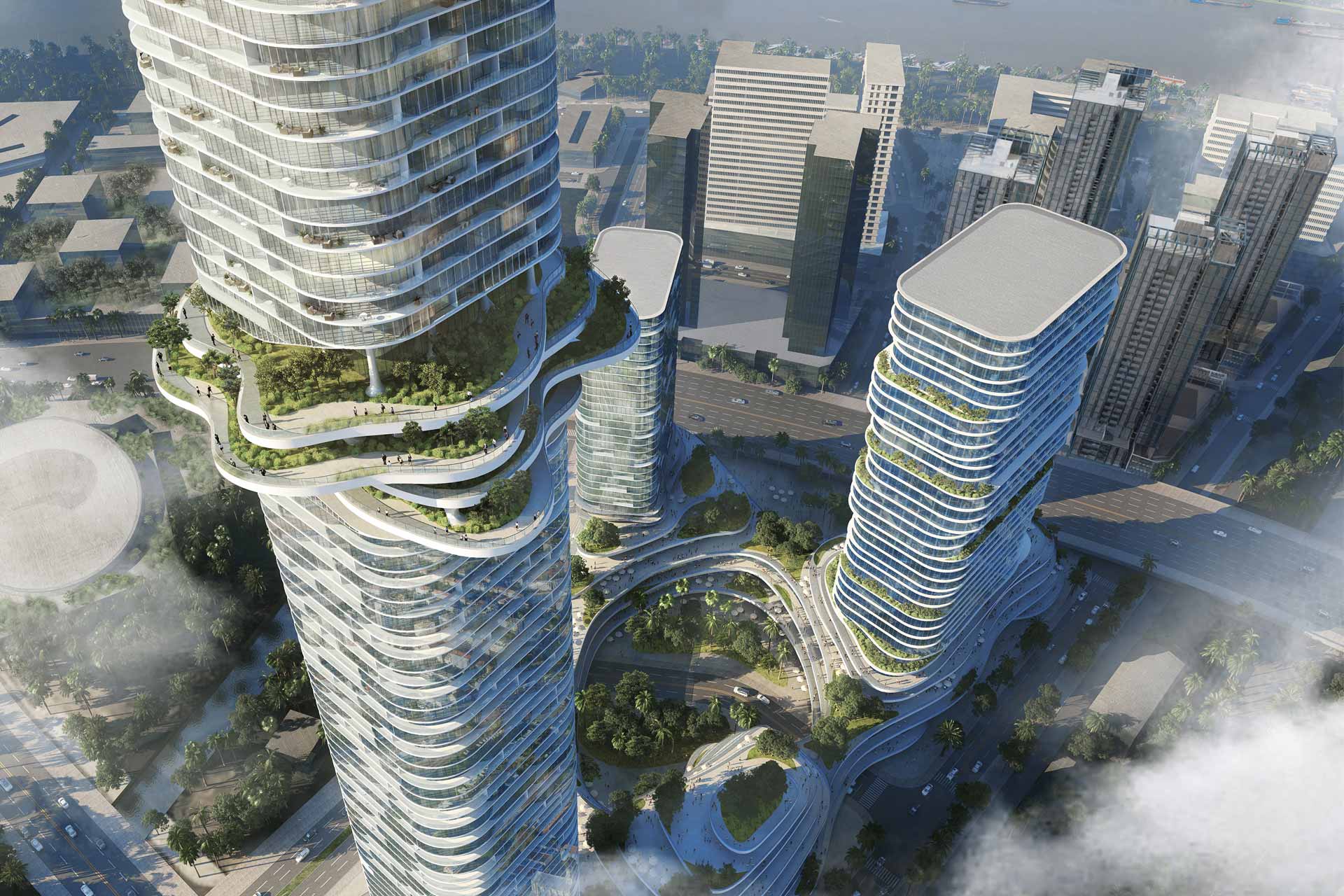

One of the larger projects on the boards is Empire City, which is spread across multiple buildings and will create an entirely new district in Ho Chi Minh City. Incorporating a hotel, residences, retail and office space, the development is anchored by an 88-storey tower that will be a new landmark on the banks of the Saigon River. Although it’s a shiny new glass-and-steel high-rise in a rapidly growing metropolis, Scheeren’s concept is once again guided by nature. “We have designed a project that really explores how Vietnam’s landscape can become an integral part of the city,” he describes, pointing out the mountain-shaped podium that echoes the country’s terraced rice fields. The multi-level podium will link the three towers and also serve as a public garden with leisure and dining facilities, while on the upper levels, hovering terraces cantilever out from the building’s central axis. “We asked ourselves, how can the verticality of a tower contain moments of spectacular nature?” says Scheeren. “So we created a floating element that we call the Sky Forest, which will be part public observation deck, part hotel and part restaurant some 300 metres up in the air.”

The overarching idea is to reflect the energy of the city’s economic growth – the development will be home to a number of major global businesses as well as start-ups and entrepreneurs – yet crucially reconnect the urban environment to the tropics. The undulating platforms of the Sky Forest feature open-air bars and landscaped walkways amongst water features and a variety of indigenous plantlife. “We wanted to capture the spirit of the tropical city, where life indoors and outdoors plays an equally important role and the presence of nature is incredibly important,” Scheeren notes, adding that the aim is to “reconcile the tension between the dense built environment and nature”.

So has the pandemic and resulting shift in the way people think about space affected the design of these ongoing projects? It would seem not. Much like Scheeren’s approach to running a global business, his ideas on the importance of space have long been ahead of their time. “On one hand, the pandemic has changed everything, but at the same time, it hasn’t really changed my architecture in the sense that I’ve been talking about this responsibility of space for the past two decades,” he concludes. “I’ve always been interested in how we live and I think the pandemic has encouraged people to consider the importance of space more than ever before. There are certain qualities that we have always tried to develop through our projects – the integration of nature, outdoor space and fresh air, and the ability to oscillate between zones of togetherness and zones of individuality. I think all of these experiences are crucial to the quality of our lives, and architecture plays a key role in achieving that.”

CREDITS

Words: Catherine Martin

Portrait Photography: © Iwan Baan

Related Posts

28 July 2021

First Look: Ole Scheeren unveils Abaca Resort

30 January 2016

100% Design

27 January 2016